“I ran for lieutenant governor [of New Mexico] in 2014; I ran for Congress in 2018. I just felt like I had an obligation. I wanted to be a leader, and I felt like I could be.”

-U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland

“I ran for lieutenant governor [of New Mexico] in 2014; I ran for Congress in 2018. I just felt like I had an obligation. I wanted to be a leader, and I felt like I could be.”

-U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland

Seeding Justice is the new name of the McKenzie River Gathering (MRG) Foundation. To announce the name change, Seeding Justice did something completely refreshing. They made a video. Yes, a video. You may wonder how refreshing a video about a foundation’s name change could be. Well, watch it.

Okay, you watched the video. Seeding Justice’s approach to telling their renaming story is creative and endearing. They turned the video call, which has become an obligatory and tedious element of American pandemic life, into something hopeful and engaging.

The video is effective because the conversations show viewers how deeply the new name connects with people who know the organization well. Seeding Justice is a powerful name. It tells you exactly what the organization does and hopes to do. The mission of Seeding Justice is “to inspire people to work together for justice and mobilize resources for Oregon communities as they build collective power to change the world.” Real people talking about how well the new name fits the organization is a lot more memorable and meaningful than a press release.

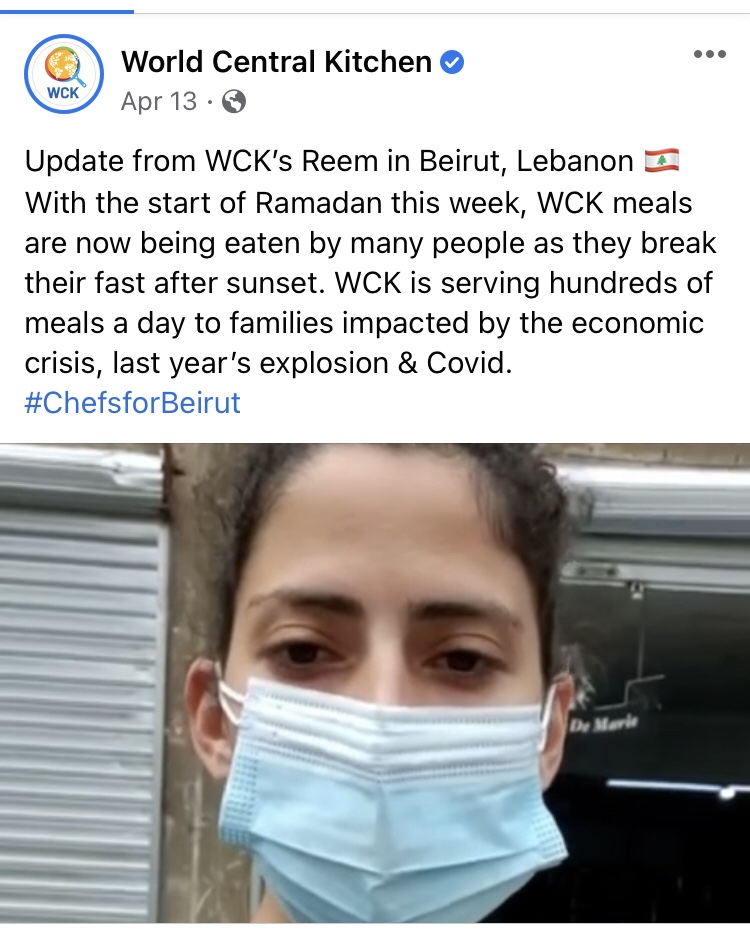

Lessons in nonprofit communications from World Central Kitchen

If you want your supporters to know why your work matters, tell them. That’s what World Central Kitchen (WCK) does. WCK isn’t the only organization dedicated to feeding people in times of crisis. They stand out because they do an incredible job of telling their story.

Yes, WCK was founded by chef José Andrés and most organizations don’t have anyone like him on their team. What they do have is the quality of their work and their unique story. A lot of organizations are great at what they do. Where they struggle is communicating why their work matters. That’s one of the many reasons a clear mission is essential. WCK’s mission and vision can be summed up in this statement by chef Andrés: “I hope you’ll dream with us as we envision a world where there is always a hot meal, an encouraging word, and a helping hand in hard times. Thank you for taking this journey with us.” Good, effective storytelling and overall organizational communications flow from mission clarity.

WCK’s social media channels feature compelling stories about real people. The emphasis is on community, connection, and hope. Whether the focus is on someone receiving food or serving food, every story demonstrates the importance of WCK’s work. There is no question about why the organization does what it does. Every post also carries an implied central message and call to action- people are hungry and in need of a hot meal right now, we’re feeding them, and you can help. This simple and effective message follows a basic message development structure:

State the problem– People are hungry and in need of a hot meal right now.

Describe your solution– We’re feeding them.

Make a call to action– You can help by (fill in the blank).

Check out these examples of this powerful strategy in action.

If you want your supporters to know why your work matters, start by telling them. Use these lessons inspired by WCK to get started-

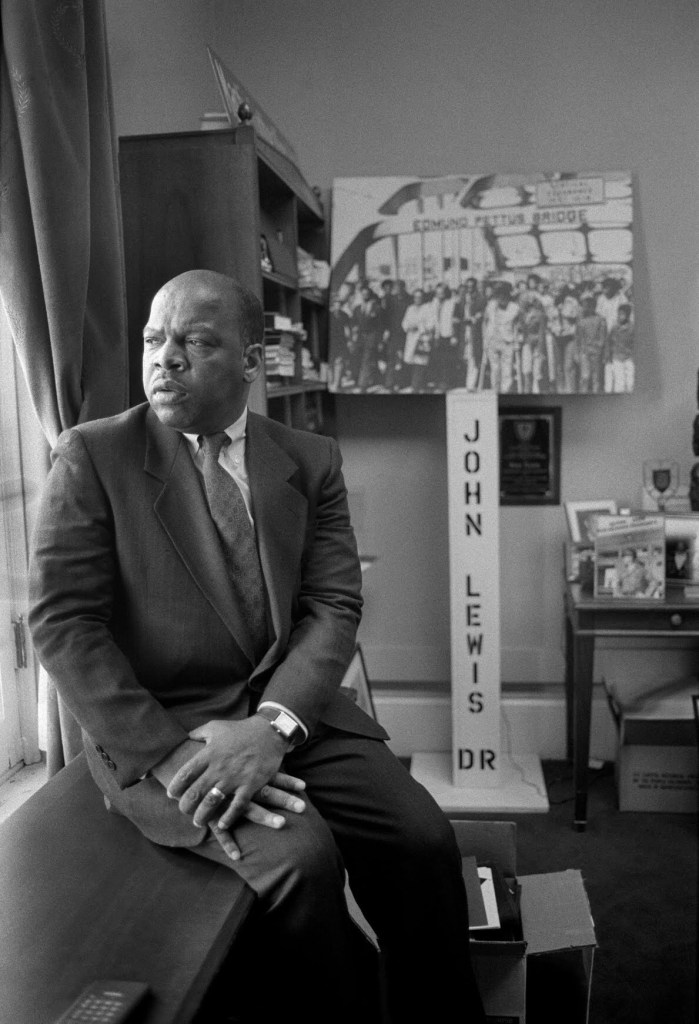

Congressman John Lewis was a joyful warrior. In celebration of his birthday, here is the essay he wrote to be published on the day of his funeral. Every word of this essay is worth reading. It is a call to action and a reminder that even in times of great despair there is hope.

“Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble. Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it.”

Congressman John Lewis

“We were frustrated with how the South had been talked about and not considered within the national political landscape. The majority of Black people live in the South. So, if you dismiss the South, you’re dismissing Black people.”

-La Tosha Brown in Marie Claire, November 10, 2020

LaTosha Brown of Black Voters Matter Fund is an expert organizer who along with her colleagues has expanded the universe of what’s possible in American politics. The work of the Black Voters Matter has been critical to the democratic victories for president and U.S. Senate in Georgia. Ms. Brown is a determined joyful warrior driven by an unyielding love for Black people and a deep passion for justice.

The cost of voter suppression is high. We see it in rates of incarceration and early death, the quality of education and access to health care, and the tattered remnants of the social safety net. When candidates are elevated to public office in voter suppressed elections, their votes reflect contempt for the people they never intended to represent.

Ms. Brown and her team’s organizing shows us what people power looks like. “Since 2016, Black Voters Matter has reached more than 7 million voters through grassroots-level outreach, campaigning and organizing. This year, their efforts were tested by the pandemic, which disproportionately hit Black communities across the country and abetted voter suppression in the form of closed precincts, longer lines and purged voting rolls.” The magnitude of what Black Voters Matter has accomplished cannot be overstated. No one changes the world alone.

2021 is going to require a collective change of consciousness and new ways of operating in the world. That change is possible and it will be hard. Who will be the helpers and the shepherds to share the vision of who we can be and keep the momentum going for better days for all of us? Some of them are already out in the world doing the work. Some of us may be among them. It’s time to look for the helpers, help them, and join them.

“The pandemic will end not with a declaration, but with a long, protracted exhalation. Even if everything goes according to plan, which is a significant if, the horrors of 2020 will leave lasting legacies. A pummeled health-care system will be reeling, short-staffed, and facing new surges of people with long-haul symptoms or mental-health problems. Social gaps that were widened will be further torn apart. Grief will turn into trauma. And a nation that has begun to return to normal will have to decide whether to remember that normal led to this. “We’re trying to get through this with a vaccine without truly exploring our soul,” said Mike Osterholm, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota.”

Where The Pandemic Will Take America in 2021

“Invest in people who don’t look like the success that you’re used to” is a brilliant piece of advice. It’s easy to overlook or dismiss people whose skills and experience don’t match up with the traditional and sometimes narrow markers of accomplishment. That thoughtful reflection by Stacey Abrams is among the many ideas to study and savor in this timely interview with Rebecca Traister in The Cut. Abrams also details the strategic organizing framework at the center of the 10 year effort to turn the tide in Georgia: voter engagement and education, building statewide infrastructure, and developing a network of funders.

Moving Georgia away from voter suppression to the practice of free and fair democratic process required a movement. To that end, Abrams first launched Fair Fight to protect voting rights and election integrity. Then came the New Georgia Project, which was started to sign-up people for the Affordable Care Act and later morphed into a voter registration organization. After establishing both groups, Abrams handed the reins over to other leaders. Fair Fight and the New Georgia Project became part of a growing coalition of organizers and organizations deeply committed and connected to communities across the state, including- the Black Voters Matter Fund, Asian Americans Advancing Justice- Atlanta, GALEO, U.S. Representative-elect Nikema Williams, Helen Butler, Rebecca DeHart, Dubose Porter, and the Georgia Democratic Party.

Abrams’ story is inspiring and powerful. “In the wake of the election, my mission was to figure out what work could I do, even if I didn’t have the title of governor,” she told Traister. No one would have blamed her for walking away from politics after losing the 2018 race for Georgia governor. The election was tainted by aggressive and blatant voter suppression. Yet her vision didn’t waver. Stacey Abrams never let other people’s assumptions dictate or define what was possible.

“Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Do not become bitter or hostile. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble. We will find a way to make a way out of no way.” -John Lewis

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” -Shirley Chisholm

The Coronavirus pandemic has exposed the inequities inherent in our nation’s systems. For people who were already experiencing the daily blunt force of inequality before Covid-19, the crisis has made meeting basic needs and maintaining well being even more difficult. Some advocates have found themselves in the challenging position of moving quickly to craft policy to help people find relief and support. The problem is these solutions are generally being developed without the meaningful involvement of the people experiencing the disparities. It’s time for advocacy to change.

Moving beyond tweaking systems to create long-term change requires advocates to collaborate with the people directly affected by the systemic inequities they seek to end. To borrow a phrase popularized by the disability rights movement, “nothing about us without us.” In some communities, advocates can have more influence on policy makers than the people who elect them. That power imbalance fosters transactional relationships in which those who experience inequality are called upon to tell their stories for an audience, not drive the discussion for potential solutions. Policies developed without the meaningful partnership of people who live closest to an issue are bound to reinforce existing inequities regardless of intent. No Child Left Behind and asset limits for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits are prime examples.

That’s why equity and inclusion must become guiding principles for advocacy. An equity statement isn’t enough. Examining the gulf between values and practices, the “what we claim to do vs. what we actually do” internally and externally (board composition, hiring practices, workplace culture, community engagement, communications, etc.) is a critical first step. If advocates are listening even a little bit, they have probably already heard about the ways their organizations may fall short of centering directly affected people or reinforcing inequities. What organizations do with what they hear matters. COVID-19 has shown us in the most cruel and mundane ways that the status quo does not work. The urgency to craft policy and strategies to navigate this crisis is real and so are the consequences of not changing the fundamental mechanics of advocacy.

It’s not too late to commit to a path of learning, reflection, and action that will result in true collaboration with communities. There will be organizational anxiety in moving beyond the learning and reflection loop to action. The process will be uncomfortable, but the discomfort is relative. While there is real pain in confronting the ways advocacy in service of policymaking has caused and may continue to cause real harm, there is material, life-altering pain in experiencing inequality.

No organization is perfect, and perfection is a fallacy often used to derail the work of equity and inclusion. The willingness to recognize and acknowledge mistakes without equivocation is not weakness; it’s an act of integrity and strength. Equity and inclusion are both processes and outcomes. A future where race, class, gender, and disability don’t predict educational, health, and economic outcomes comes from the foundational practice of sharing power and co-designing solutions with the people directly affected and historically excluded from decision making. In the words of US Representative Ayanna Pressley, “those closest to the pain should be closest to the power.” When advocacy is rooted in equity and inclusion, it is just.

Recommended reading:

Race is not the reason Black Americans have a higher risk of dying from the coronavirus. It’s racism.

#WeAreEssential: Why Disabled People Should Be Appointed to Hospital Triage Committees

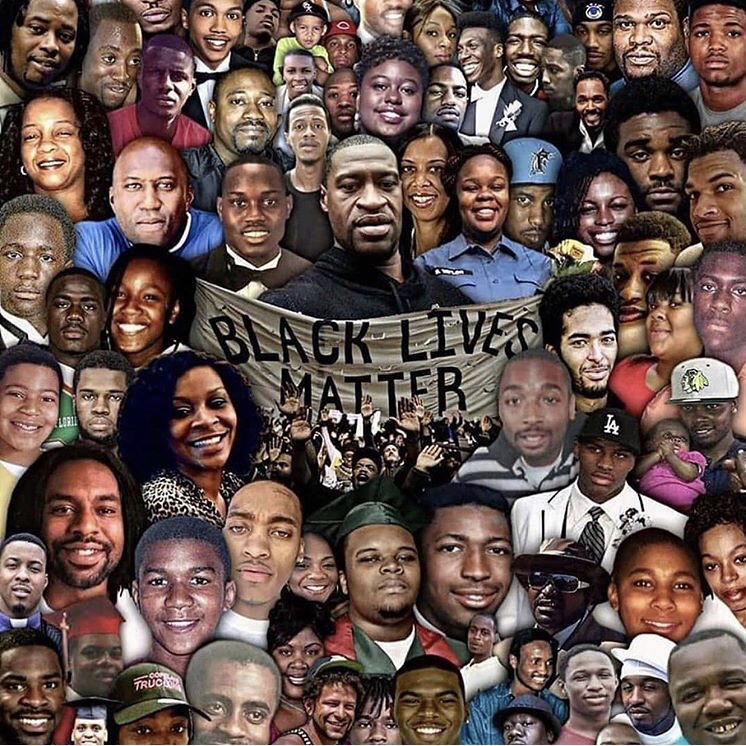

A few days ago, I wrote this letter for the City Club of Portland about the historical context of where we are now as a nation.

“Mr. Floyd is the most recent in a long line of Black people who have been killed by police and vigilantes who take the mantle of authority over the lives of Black people. Over the last few weeks, we’ve heard in quick succession about the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, a young man who was hunted down by three white men as he jogged in Georgia; Breonna Taylor, a Louisville EMT who was killed by police while she slept; and Tony McDade, a trans Black man killed by police in Tallahassee.

These murders are not anomalies. There is a long, bloody, and brutal history of disregard and open hostility for Black life in the United States.”

Read the full post: https://www.pdxcityclub.org/our-role-in-this-moment/